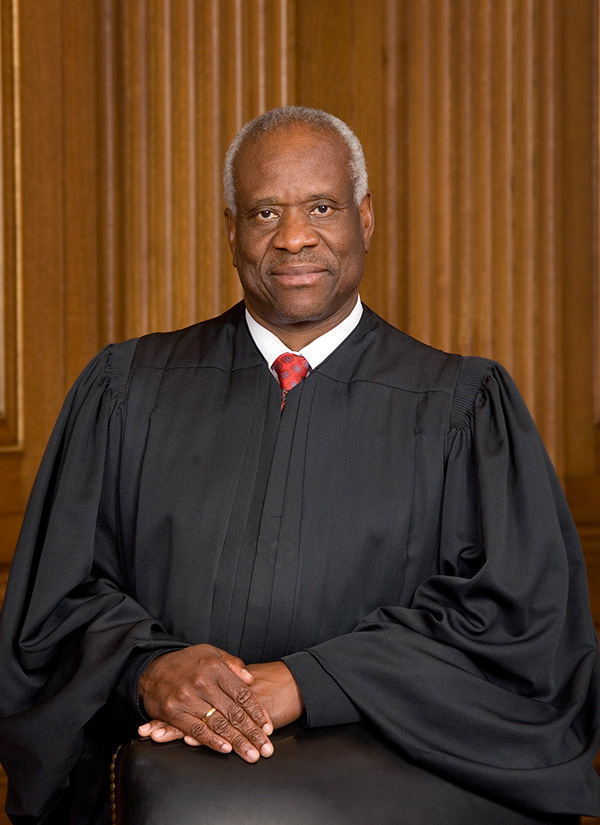

Clarence Thomas (1948–)

2012-09-16 08:06:16

Clarence Thomas, the second African American to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States, was born in 1948 in the economically deprived town of Pin Point, Georgia. Abandoned by his father and given up by his mother, Thomas was raised by his maternal grandparents in a segregated society. Through hard work, sacrifice, and sheer force of will—his own and that of his grandfather—he graduated with honors from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and then from Yale Law School in New Haven, Connecticut. He held a number of government posts prior to being appointed in 1991—after a bitter confirmation battle—to the nation’s highest court, including the chairmanship of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Justice Thomas is most famous for his civil rights opinions, especially those criticizing Affirmative Action. He has written a number of important civil liberties opinions as well.

Clarence Thomas (1948–)Justice Thomas’s most significant free speech opinion is almost certainly his concurring opinion in the 1996 Commercial Speech case 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. State of Rhode Island (517 U.S. 484, 1996), in which he called for the abandonment of the distinction in the level of judicial protection afforded to commercial and nonCommercial Speech. He wrote: ‘‘Nor do I believe that the only explanations that the Court has ever advanced for treating ‘commercial’ speech differently from other speech can justify restricting ‘commercial’ speech in order to keep information from legal purchasers so as to thwart what would otherwise be their choices in the marketplace.’’ Thomas reiterated his call for increased judicial protection of Commercial Speech in three subsequent cases: Glickman v. Wileman Bros. & Elliot (1997), Greater New Orleans Broadcasting Association v. United States (1999), and Lorillard Tobacco Company v. Reilly (2001). No other member of the Court has concurred in his reasoning.

Clarence Thomas (1948–)Justice Thomas’s most significant free speech opinion is almost certainly his concurring opinion in the 1996 Commercial Speech case 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. State of Rhode Island (517 U.S. 484, 1996), in which he called for the abandonment of the distinction in the level of judicial protection afforded to commercial and nonCommercial Speech. He wrote: ‘‘Nor do I believe that the only explanations that the Court has ever advanced for treating ‘commercial’ speech differently from other speech can justify restricting ‘commercial’ speech in order to keep information from legal purchasers so as to thwart what would otherwise be their choices in the marketplace.’’ Thomas reiterated his call for increased judicial protection of Commercial Speech in three subsequent cases: Glickman v. Wileman Bros. & Elliot (1997), Greater New Orleans Broadcasting Association v. United States (1999), and Lorillard Tobacco Company v. Reilly (2001). No other member of the Court has concurred in his reasoning.

Justice Thomas has taken an equally dramatic position in three cases involving political speech. In Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee v. Federal Election Commission (1996), Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC (2000), and Federal Election Commission v. Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee (2001), he called, in a series of dissenting and concurring opinions, for the overruling of Buckley v. Valeo (424 U.S. 1, 1976), the landmark Burger Court decision that, among other things, upheld Federal Election Campaign Act provisions limiting contributions by individuals to any single candidate for federal office. He insists that Buckley was a ‘‘flawed decision’’ riddled with ‘‘analytic fallacies’’ and that it was inconsistent with the framers’ position that political speech is the ‘‘primary object’’ of First Amendment protection.

As Justice Thomas’s political speech opinions make plain, he is not afraid to call for the overruling of precedent. His one-paragraph concurring opinion in Eastern Enterprises v. Apfel (524 U.S. 498, 1998) is further proof. In that case Thomas joined the controlling opinion of the Court that the federal statute in question effected an unconstitutional taking. He wrote separately to suggest that the case could have been decided on the basis of the ex post facto clause because that clause should be applied in the civil context and not simply the criminal context. Calder v. Bull, which was decided in 1798 and was one of the early Court’s most important decisions, limited the clause to the criminal context, but Justice Thomas stated that he would be willing to overrule the more than two-hundred-year-old precedent.

The justice also has written powerful opinions in the areas of religious freedom and abortion. For example, he joined the Court’s opinion in Rosenberger v. University of Virginia (515 U.S. 819, 1995) striking down a state university’s policy that forbade student activities fees from being used to fund student groups engaged in religious activities. He wrote separately to make clear that, in light of his reading of history, the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment only forbids direct government aid to a favored religion.

With respect to abortion, Justice Thomas penned a strong dissent in the ‘‘partial birth’’ abortion case Stenberg v. Carhart (530 U.S. 914, 2000). He called that procedure ‘‘infanticide’’ and declared that Roe v. Wade (1973), the Burger Court’s polarizing abortion decision, was ‘‘grievously wrong.’’

Justice Thomas was the most conservative member of the Rehnquist Court, and all of his major civil liberties opinions during his ten-plus years of service have generated strong reaction from other members of the Court, scholars, interest groups, and the press. However, his most controversial opinion was issued during his first term. The case, Hudson v. McMillian (1992), found the Court holding that a prisoner need not always suffer a ‘‘significant’’ injury to prevail on an Eighth Amendment’s cruel and unusual punishments claim. The justice did more than disagree with the Court’s conclusion: He spent eleven pages in the U.S. Reports explaining why, as a matter of constitutional text and history, the Eighth Amendment does not apply at all to the conditions of a prisoner’s confinement.

If one relied solely upon what his critics said that Thomas said in his Hudson dissent, one might be left with the impression that the justice would have personally taken a few swings at the prisoner in question if he had been in the room when the guards assaulted him. Nothing could be further from the truth. Thomas condemned the mistreatment of prisoners in the strongest possible terms. He simply argued that state law and perhaps other provisions of the federal Constitution were where prisoners should turn for redress.

More recently, some commentators have begun to take seriously Justice Thomas’s contributions to civil liberties jurisprudence. For example, famed liberal columnist and First Amendment icon Nat Hentoff, who had proclaimed during the justice’s early years on the Court that ‘‘no new justice has ever done so much damage so quickly,’’ now maintains that he is the Court’s staunchest defender of the freedom of speech.

The vast majority of the justice’s civil liberties opinions have been concurring and dissenting opinions. However, he has begun to persuade some of his colleagues on the Court, as he also has done with at least some of his former critics, of the power of his vision of the Constitution’s civil liberties guarantees. Justice Thomas is still a relatively young Supreme Court justice and only time will tell how much he can shape this fundamental area of American law.

SCOTT D. GERBER

References and Further Reading

- Gerber, Scott Douglas. First Principles: The Jurisprudence of Clarence Thomas. New York: New York University Press, 1999; expanded edition, 2002.

- Hentoff, Nat. ‘‘First Friend: Justice Clarence Thomas Has Written as Ardently in Defense of Free Speech as Liberal Icon William Brennan, Jr. Ever Did.’’ Legal Times, 3 (July 2000): 62.